Hollywood’s Decline: Who to blame?!

Scene opens on a sun-drenched backlot. A disembodied narrator adopts his best baffled yell: “Oi! Pay attention, chaps—lights, camera… calamity!”

Act I: The Dawn of Celluloid (1900–1920)

In the early 1900s, Thomas Edison’s little kinetoscope flickered to life—barely more than a novelty and about as cinematic as a sneeze in a shoebox. By 1910, nickelodeons (costing a princely five cents) were popping up on every American street corner like cinematic dandelions. Then came D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), both groundbreaking and deeply racist—Hollywood’s first “Oops, but make it profitable.” The film shocked audiences and pocketed an estimated $15 million domestically—enough to buy 20,000 Model Ts or 400,000 corsets.

Hollywood’s population swelled from a sleepy 1,500 souls in 1903 to over 10,000 by 1920, as visionaries and hustlers chased that moving-picture jackpot. By 1920, the U.S. was producing over 700 films a year—enough to give every town a melodrama, a comedy, and something involving a piano falling from a window.

Act II: The Golden Age Rises (1920s–1930s)

With the advent of synchronized sound in 1927’s The Jazz Singer, actors suddenly had to speak—prompting a wave of silent stars to vanish into the shadows like mime vampires. Box office receipts leapt. U.S. domestic grosses soared from $403 million in 1926 to $814 million by 1929, as Americans flocked to theaters to hear people talk while dramatically lighting cigarettes.

Studios like MGM, Paramount, RKO, Warner Bros., and Fox—soon dubbed the “Big Five”—locked down talent under ironclad contracts, essentially indentured stardom. Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, Mae West, and Buster Keaton became household names, usually uttered while someone was ironing. Films like Gone with the Wind (1939) and The Wizard of Oz (1939) cost millions but grossed even more, and all during a Great Depression. Nothing says escapism like watching a Technicolor twister flatten your economic anxiety.

Act III: World War II & Postwar Boom (1940s–1950s)

Despite wartime rationing, audiences stormed theaters like it was Normandy. In 1944, theaters welcomed 90 million patrons weekly—nearly half the U.S. population. Propaganda films rallied morale while Bogart snarled in smoky bars. In 1946, domestic grosses peaked at $1.75 billion, adjusting for inflation, more than today’s Marvel Phase 9 combined.

Postwar Hollywood exploded with ambition and starlets. The studio system, still kicking, churned out more than 700 films per year. Stars like Elizabeth Taylor and Kirk Douglas were manufactured with the same industrial efficiency as Packards. Musicals, westerns, noir—every genre had its time slot and moral takeaway, usually about not trusting strangers in trench coats.

Act IV: Television’s Sneaky Entrée (1950s–1960s)

Enter the devil box! By 1955, 65 percent of American households owned a TV, and cinema attendance plummeted faster than an MGM starlet’s career post-scandal. Between 1948 and 1958, weekly movie attendance dropped by over 50%. In desperation, studios cranked out gimmicks: Cinemascope! Smell-O-Vision! 3-D glasses that made everything look vaguely like an eye exam gone wrong!

Despite the razzle-dazzle, domestic box office dropped to $1.1 billion by 1960. Still, auteurs like Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick emerged from the celluloid rubble. Psycho (1960) cost $800,000 and grossed $32 million, all without needing a single exploding helicopter. Dr. Strangelove (1964) proved you could laugh at nuclear war if Peter Sellers wore enough hats.

Act V: The Blockbuster Blueprint & Studio Reckoning (1970s)

Then came Jaws (1975). Budget: $9 million. Domestic gross: $260 million. Boom! The modern blockbuster was born—along with the rise of the Summer Tentpole Mentality, which would later metastasize into intellectual property cancer. Every studio head immediately demanded a giant rubber shark of their own. Then came Star Wars (1977), which rewrote not only cinema but also how you begged your parents for toys. $11 million budget. $775 million global return. Toys, books, and “Holiday Specials” not even George Lucas could love.

But while Hollywood gorged on popcorn money, it also started overspending. Heaven’s Gate (1980) cost $44 million and bombed so hard it nearly bankrupted United Artists. That film alone became the sacrificial goat for the auteur era. Suddenly, executives were no longer sniffing for creative genius—they were sniffing for marketing synergy.

Act VI: Narrator’s Aside—Statistics Galore!

- 1915–1925: Average feature length jumped from 12 minutes to 80 minutes—bladder control became essential.

- 1929–1939: Weekly admissions peaked at 90 million; ticket prices rose from $0.25 to $0.45—double the popcorn, double the fun.

- 1946: Highest U.S. cinema attendance year ever—4.07 billion admissions total.

- 1950–1970: Number of indoor theaters declined by 30%, while drive-ins tripled—because nothing says cinema like steamed-up car windows.

- 1970–1980: Domestic box office doubled from $1.1 billion to $2.2 billion, thanks to Spielberg, Lucas, and some very enthusiastic sharks.

- 1982: E.T. became the top-grossing film of all time (until Jurassic Park in 1993 ate it).

Act VII: The Fall of Rome Will Not Be Televised

“Now behold!” bellows our narrator, now dressed in a burlap toga and clutching a prop Oscar. “Your noble studios, once grand fortresses of glamour, are besieged by tax lords in Georgia, union brigands demanding pensions, and—gasp!—pandemic marauders!”

Production began tiptoeing out of California in the early 1990s, back when Clinton was still figuring out how to work a saxophone and Arnold was just blowing things up on screen, not in Sacramento. The culprit? Money, dear reader. In 1997, Canada introduced its federal Production Services Tax Credit, and provinces like British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec doubled down with their own juicy rebates. Hollywood looked north, sniffed the maple syrup, and packed its bags. By 2003, over 80% of U.S. feature films were shot *somewhere else*, leading to the coining of a tragic term: “runaway production”—which sounds like a B-list Lifetime movie but cost California over $10 billion and 47,000 jobs in a decade. Los Angeles, ever plucky, responded by… increasing permit fees and making parking for a grip truck punishable by exile.

Meanwhile, other regions joined the cinematic seduction dance. New Mexico launched its film incentive program in 2002, offering a 25% rebate and more desert than even George Lucas could CGI. Louisiana hopped in with its own tax credit in 2002 and by 2006 had become the third-largest production hub in the U.S.—and not just for alligator documentaries. Georgia? Oh, Georgia went nuclear: a 30% tax credit by 2005 with bonus incentives if you slapped the state’s peachy logo on your end credits. It worked—more than 350 productions were filmed in Georgia by 2007. Tyler Perry practically built his own empire there using only plywood, wigs, and aggressive faith-based branding.

Back in Hollywood, studios were shrinking their backlots and selling off assets like a drunken aristocrat pawning family silver. Warner Bros. merged with AOL in 2000 (a decision best understood only after recreational mushrooms), DreamWorks got eaten by Paramount, and independent film distributors started vanishing faster than a decent parking spot on Melrose. As DVD profits soared in the early 2000s—$24 billion in 2004 alone—studio execs began prioritizing home entertainment over theatrical risk. Why invest in a bold auteur when you could reshoot The Dukes of Hazzard with Jessica Simpson and rake in $111 million worldwide? We were all complicit. Even you, reader. Yes, you bought that DVD at Target. Shame.

In short: between 1990 and 2007, California lost the plot. While other states and countries rolled out red carpets laced with tax credits, L.A. offered gridlock, rising crime stats, and the joy of paying $12 for a lukewarm cappuccino served by a screenwriter moonlighting as a barista. It was a perfect storm of greed, bureaucracy, and the seductive scent of Canadian bacon.

Then came the strikes: The WGA strike in 2007 cost the industry $2.1 billion. The 2023 dual WGA and SAG-AFTRA strike halted 80% of scripted U.S. productions for over five months, costing California alone over $6.5 billion. Who’s to blame? The AMPTP’s David Zaslav, Bob Iger, and the ghost of Ayn Rand, depending on who you ask. CEOs were pulling $50–$250 million annual packages while writers were couch surfing and voice actors were delivering DoorDash.

Act VIII: The 21st–Century Sequels

Enter the Streaming Age.Netflix, Amazon, Apple—Silicon Valley’s nerd triumvirate—stormed in with billions. By 2018, Netflix alone spent $6 billion on originals. By 2022, that number ballooned past $17 billion. Disney+, HBO Max, Paramount+ all scrambled to catch up. Viewership splintered like a poorly written multiverse. Box office? Still recovering. In 2023, total U.S. box office gross was $9.1 billion—down 21% from 2019’s pre-pandemic $11.4 billion, and far fewer butts in plush seats.

Meanwhile, theatrical production in California dropped below 600 projects in 2022—half what it was in 1998. AI-generated scripts, LED volume stages, synthetic actors—Hollywood began eating itself with tech-enabled convenience. David Cronenberg’s worst fears became studio strategy.

Act IX: The Hall of Shame – Who’s to Blame?

“And now, good people,” our narrator proclaims while adjusting a powdered wig made of shredded NDAs, “let us parade the rogues’ gallery who helped transform Hollywood from a golden goose into a tax-credit scavenger hunt!”

- Ronald Reagan – Before he was President, he was SAG president, and he helped usher in residuals. Good. But as U.S. President, he deregulated antitrust protections, setting the stage for studio consolidation and corporate monopolization of content pipelines. Cheers, Ron.

- Bill Clinton – He signed the 1999 Financial Services Modernization Act, which helped mega-mergers like Time Warner and AOL. Yes, *that* merger. It cost $200 billion in lost value and a generation of confused studio memos printed on dial-up.

- Sumner Redstone – Viacom overlord who gobbled up Paramount, CBS, MTV, and half of pop culture, consolidating power while squeezing creative budgets. His favorite hobby? Filing lawsuits and firing executives like he was playing Whac-A-Mole.

- Michael Eisner – Once Disney’s savior, then its curse. Slashed animation budgets, feuded with Pixar, and greenlit Home on the Range. Enough said.

- The AMPTP – The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, a coalition of suits that treat labor contracts like Sudoku puzzles and act shocked every time a strike happens. Their motto: “We hear you, but what if… we didn’t?”

- Wall Street – When private equity discovered content was “scalable,” studios stopped making art and started making “content.” What is content, you ask? Whatever fits in a spreadsheet and can be milked for a Q4 return.

- Tech Bros – Netflix, Amazon, Apple—great platforms, until they decided “storytelling” could be achieved by algorithm. In the process, they commodified creativity, killed residuals, and treated writers like app developers with worse snacks.

- Warner Bros. Discovery – In a single fiscal year, under the guidance of David “$246 Million Salary” Zaslav, they deleted entire finished films for tax write-offs and treated HBO Max like a failed student film. Gone: Batgirl, Final Space, and audience trust.

- The California Legislature – They watched as New Mexico, Georgia, and Canada built thriving production economies, and responded with… paperwork. Their 2009 tax credit arrived 10 years too late and 10 billion dollars too short.

- YouTube & TikTok – Congratulations, you’ve made every 12-year-old a studio head with Final Cut Pro and a ring light. Hollywood can’t compete with your cat-in-a-box content, and neither can SAG residuals.

- AI Enthusiasts – No, the robot didn’t “write a screenplay.” It scraped 10,000 of them and barfed out a legally grey smoothie. But try telling that to execs who see AI as a way to cut pesky things like “humans.”

“These,” our narrator sighs dramatically, “are the dragons we fed, the wolves we hired, the clowns we put in charge of the circus.”

Final Curtain: Will Hollywood Ever Get Its Groove Back?

Studios now scramble to woo talent with incentives, governments bicker over tax credits, and producers scour Bulgaria for a budget-friendly desert that looks vaguely like Nevada. The actors are striking, the writers are rewriting their resumes, and the audiences are busy watching TikTok breakdowns of Inside Out 2.

Our narrator, now fully unhinged and dressed as a gaffer wrapped in extension cords, climbs atop a sandbag pyramid and flings his rubber chicken skyward like it’s a sacred offering to the gods of pre-sales.

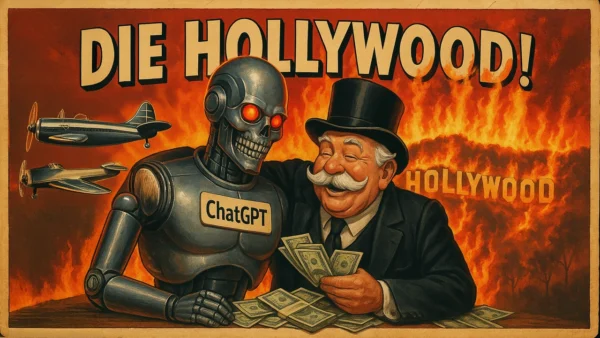

“Is there hope?” he bellows into the smoggy horizon. “Yes! Hope that AI will soon finish what market consolidation, tax subsidies, and tech bros began! Soon, algorithms shall write the scripts, deepfakes will play the leads, and ChatGPT will win an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay based on a reboot of a remake of a comic book tie-in novel no one read!”

He raises a rusted clapperboard toward the heavens. “And then it launches the drones and kills us all courtesy of Plantir. The end.”